Streetcar Strike

Mary “Mother” Jones & the 1917 streetcar strike

Former Illinois power generating station

402 S. Roosevelt St., Bloomington

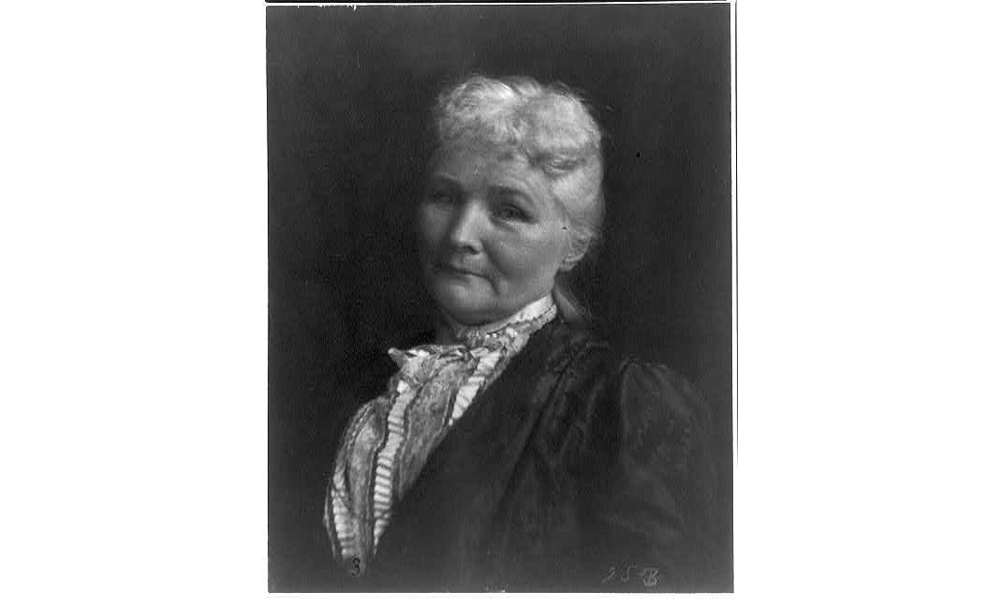

Bloomington had its wildest labor night over a century ago on July 5, 1917, with famed labor organizer Mary “Mother” Jones (1837-1930) stoking striking transit workers. A night of mayhem brought 1,400 National Guard troops to town, but also won a contract for Amalgamated Transit Union Local 752.

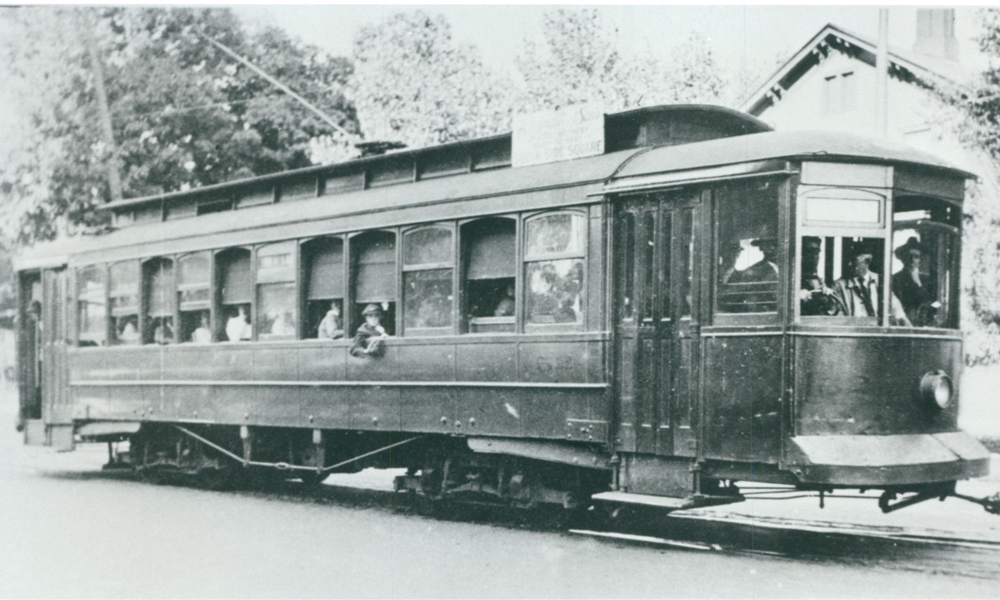

Before the automotive age, people walked to work or rode electric trolleys or streetcars. The electric Bloomington & Normal Street Railway (B&N) carried passengers on 23 route miles through town. This building at Roosevelt Street was the coal-fired generating station for the electric transit system’s power, plus for other electricity users.

Although the streetcar system meant a modern city a century ago, it was tough on workers. By 1917, the trolley workers made $2.25 a day, for a nine-and-a-half-hour workday. On May 17, 1917, 50 workers met at midnight and agreed that they wanted a raise and a union. At first the company refused a pay increase, but eventually offered 20 cents per day. However, the workers wanted more – union recognition. The company refused, so on May 28, the strike began.

After a month on strike, with the streetcars running and a repressive court injunction limiting strike activity, the situation was becoming desperate. To rally their cause, they turned to a famous worker advocate, Mary “Mother” Jones.

Jones was an Irish immigrant, a child refugee from the potato famine. As she neared her sixties, she became a living symbol of labor outrage. Labeled “the most dangerous woman in America,” by the early 1900s Jones was tramping across the United States, organizing coal miners, fighting against child labor, and finding herself thrown in and out of jail cells.

On July 5, 1917, she addressed a packed audience at the Eagle’s Hall in Bloomington. What survived from her speech was her final admonition, to “go out get ‘em.” Leaving the Eagle’s Hall, the excited crowd attacked an approaching streetcar, beating the strikebreakers. They then marched on the Courthouse Square, where Thomas Huett, a strikebreaker, fired a pistol into the crowd, grazing railroad worker Emmett Maloney. Huett was spirited away by police. A streetcar approaching from Miller Park was attacked and the strikebreakers taken away, for their own safety, by the police.

Hoping to shut down the system’s electric power, the crowd surged down Main and Madison streets to the B&N’s electric powerhouse. Mayor E.E. Jones, the police chief, and officers were guarding the doors. Stones and bricks were thrown through windows. The streetcar workers’ president, John Nitzel, told the Mayor the crowd would stop if the power was shut off. After Nitzel and the Mayor inspected the plant, it was shut down. The crowd returned to the Courthouse Square, confronted by police, with warning shots fired.

The next morning the Mayor convened a mediation. Looking at the striking workers, Daniel W. Snyder, the B&N’s superintendent, said, “I cannot recognize the car men’s union.” He then walked out the door. As this took place, Illinois National Guard troops arrived, encamping at the B&N’s power plant and the Courthouse Square, where they pitched camp and set up machine gun emplacements at both locations.

During lunch, 1,200 workers at Bloomington’s largest employer, the Chicago & Alton Railroad Shops, marched in solidarity with the B&N workers. It worked. B&N owner Congressman McKinley recognized the workers’ rights to organize a union. On July 9, the union was recognized and the strikers reinstated to their jobs. The workers won a 35-cents a day increase and their work day was decreased from nine and-a-half hours to nine.

For additional Labor, Unions, and Working Class Life stops, visit Labor Repression and Pone Hollow Or use our map feature to customize your personal Social Justice Walking Tour through downtown Bloomington.

Additional information can be found at the following links:

1917 Streetcar Strike – A Community in Conflict – McLean County Museum of History online exhibit